CHAPTER XV(Pages 292 to 311)

|

|

To see Ani properly you must spend at least one night there, but I cannot describe that experience as exactly blissful. I advise other travellers to bring their own provisions. The aged monk, who with a couple of peasants form the whole population of the old Armenian capital, is friendly and hospitable, and places all he has at the disposal of the visitor, but it is very little. He lives in a one-storied stone house near the cathedral, where a large but very dirty room, with four beds in it, serves as bedroom and dining-room for guests. A visitors' book is kept, going back a good many years. Most of the entries are in Armenian, and therefore to me undecipherable. A good number are in Russian, and a few in English, French, German, Italian, &c. I need hardly say that I found the record of the visit of the two English spinsters touring through the land of Ararat. Where does one not come on the traces of that most enterprising species of the human race, the [page 296] British spinster? Surely their tracks mark out the path of Empire, for they, like the men in Kipling's poem, belong to "The legion that never was 'listed, That carries no colours nor crest." Some of the visitors have been inspired by the ruins to lapse into poetry, of the usual variety common to visitors' books all the world over. But I could not help being struck by the small number of people who visit this wonderful city. For whole months sometimes only two or three names are recorded.

|

Before describing the ruins themselves I must say a few words on the situation and history of Ani. The Arpa Chai has cut its way by a deep, sinuous canon across the plain at this point, and is joined by a small stream, also in a deep ravine, called the Aladja Chai. On the promontory formed by the meeting of the two rivers Ani has been built. The third side is indicated by a slight depression of the soil across which a fosse was excavated, and two ravines with a tiny torrent in each join the rivers. A platform is thus formed which offered excellent opportunities for defence in days when there was no artillery to dominate it from the neighbouring heights. In fact, Ani was originally a fortress, before it became the capital of a kingdom. The enclosure is not flat, but like the rest of the plain, rolling and irregular, with several sharp eminences and depressions. The soil is of a rich brown colour, very stony in parts, and covered with a pale yellow grass, which serves to [page 297] intensify the appearance of dry barrenness. In the middle of this desolate space stand the ruins of churches and palaces without number, some mere vestiges of broken masonry and formless heaps of stones, others in their general features almost intact. All around, as far as the eye can reach, the plateau extends in vast folds and waves like the ground-swell of a sea. Due east rises the mass of Alagoz, on which a few small snow-fields gleam brightly. To the south-east is Ararat, but it is hidden from us by a number of minor eminences.

The history of Ani [note 2] is closely bound up with that of the Armenian kingdom in its later phase. In the early days of the Arsakid dynasty we have no record of Ani. After the collapse of that house the country was conquered by the Persians and formed part of their Empire, while the western provinces were annexed to the dominions of the East Roman Caesars. In the 7th century it was overrun by the Arab invaders and eventually annexed to the Baghdad Khalifate. The conquerors persecuted Christianity and attempted, though without success, to exterminate it - the Persians in the interests of the religion of the Magi, the Arabs in those of Islam. Under the Khalifs the country was ruled by Mohammedan governors, who in later times permitted the inhabitants a certain amount of autonomy. The Armenian people were under a feudal regime at the head of which we find certain great families; the most important of these are the Bagratids, who were of Jewish origin, and the [page 298] Artsruni. The former gradually succeeded in dominating the eastern half of Armenia, first as mere representatives of the Khalifs and the latter as more or less independent kings, while the latter ruled in the west.

For a short period the Bagratid kings succeeded in bringing the whole of Armenia under their sway; but from the 8th century onward the history of the country is a series of wars and revolutions, in which domination is divided between and fought for by the Arabs, the Greek Emperors, the Seljuk Turks, and various native princes. The first Bagratid king was Ashot I. (856-889), under whom the kingdom of Armenia extended to Erzerum in the west and to Caucasus and the Caspian in the east. With the advent of his successor Sembat I. (890-914) begins the series of invasions by the Arab governors of the province of Azerbajan, which were to play such a part in the subsequent history of the country. The war waged by the men of Azerbajan, Persians, Arabs, Kurds, and Tartars, against the Armenians may indeed be said to have continued with few interruptions for sixteen hundred years. Its latest phase is the present struggle in the Eastern Caucasus, for most of the Tartars there are of the Azerbajan stock. Under Sembat I Ani, then only a fortress, was given over to the Georgians. It was subsequently regained by the Armenian kings, and already began to acquire importance on account of its churches and monasteries. Ashot III was anointed king of Armenia at Ani in 961. He it was who converted it into a splendid city and made it the capital of [page 299] his kingdom. His son and successor, Sembat II. (977-989), enlarged and beautified it. Gaghik I (989-1019) completed the fine cathedral, built the church of St. Gregory the Illuminator, and transferred the Patriarchate to Ani. During the reign of Ashot IV, in 1022, Ani was captured and pillaged by the King of Georgia, the first of its many conquerors. But it soon fell again into the hands of the Armenians. This part of Armenia came to be designated the kingdom of Ani or Shirak, to distinguish it from the Armenian kingdom of Van or Vagarsapan. Ashot gave it over by his will to the Greek Emperors; the Greeks afterwards claimed the heritage, and in 1041 attempted to seize Ani, but were defeated. Here we see one of the earliest manifestations of the hatred of Armenians and Greeks, which, like that of Greeks and Slavs in the Balkans, contributed in no small degree to the conquest of all these lands by the Ottoman Turks. Now begins the most woeful period of Armenian history.

In the west the Ottoman Turks make their appearance and begin their ravages, while in the east Toghrul Bey conducts his hordes of Turkomans from Azerbajan to Nakhitchevan and the Araxes valley. Gaghik II (1042-1045) defeated the Turkomans near Erivan, but failed to stop their advance. In 1045 the Greeks succeeded in seizing Ani by treachery, which for some time was to be ruled by Greek Governors. Ten years later a host of Seljuk Turks massacred a number of Armenians outside the walls of Ani, and in 1064 Alp Arslan, the Seljuk Sultan, made a formidable attack on the city. [page 300] After a twenty-five days' siege the Turks penetrated within the walls, each man, according to Matthew of Edessa, carrying a knife in each hand and a third in his teeth. The garrison took refuge in the citadel, and the citizens were massacred by the thousand. Ani was afterwards purchased of the Seljuk Sultan by the Kurdish Mohammedan family of Beni-Cheddad, who formed a small vassal state, and dragged on an eventful and stormy existence until nearly the end of the 12th century. In 1124, David, King of Georgia, took over the city and held it for a short period; his successor, George III, captured it in 1161, restored it to the Kurds four years later, and seized it again in 1173. In the reign of the celebrated Georgian Queen Thamara (or Thamar), the people of Ani were massacred by the Emir of Ardabil in Azerbajan. In spite of these repeated sacks the city seems to have been still rich and populous ; but in 1239 it was captured and plundered once again by the destroying Asiatic hordes of Genghis Khan. In 1319 the final catastrophe came in the form of an earthquake, which wrought terrible havoc. Although the city seems to have been partly inhabited for a few years more [note 3], it never recovered, and was eventually abandoned. So it has remained for close on six centuries, deserted, solitary, and silent, a monument to the past greatness and magnificence of a people. Ani must have been a splendid city indeed in its halcyon days. Mass was celebrated, says Matthew of Edessa, in a thousand and one churches, many of them of great wealth and magnificence, as the ruins [page 301] attest to this day. Merchants from all parts of the Middle East flocked to its markets, and a teeming busy population, said to have numbered 100,000 souls in the 11th century, filled its streets. The whole enclosure of the ruins is not very large-about three and a half miles in circumference. Mr. Lynch [note 4] suggests that a great part of the inhabitants must have dwelt outside the walls. The existence of large numbers of cave dwellings in the ravine of the Aladja Chai, many of them inhabited to this day, bears out this view.

The character of the architecture is very striking, especially to those unfamiliar with the Armenian-Georgian style. Its direct descent from that of Byzantium and its resemblance to Norman, to which I have alluded in a previous chapter, are particularly remarkable, although there are many individually Armenian characteristics. The masonry is, as usual, extremely solid and of excellent quality. The walls are composed "of an inner core of conglomerate, faced on either side with rectangular blocks of hewn stone," alternately red and dark grey in some buildings, wholly grey, red, or of a brownish yellow in others. The adornments are severe and simple, but beautifully moulded and always in exquisite taste. Besides the buildings which are still standing excavations are constantly bringing to light the foundations of further edifices. The greater part are churches and monasteries, although the city walls and the castle are among the most conspicuous. Of private dwellings there are very few traces, whence Mr. Lynch argues that they were probably built of inferior material. [page 302]

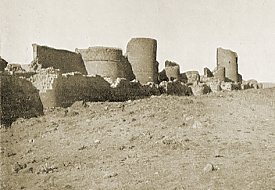

The first building which one sees on reaching Ani is the outer wall. Nowhere, except at Constantinople, have I seen more splendid defences of a mediaeval city. For about two-thirds of a mile they are still standing, and broken fragments of them extend along the whole length of the circumference of the city and descend into the ravine of the Arpa Chai. The part which is still more or less intact is that defending the almost level space between the two rivers, where the strategic position was naturally weakest. We have a long stretch of double walls and forty huge round towers at short intervals. The chief entrance is by a small gateway in the outer wall leading into the enclosure; we then turn to the left for a short distance until we come to a second larger gate in the inner wall flanked by two massive towers. There is a bas-relief of a lion and several inscriptions in various characters on this part of the fortifications. The walls were first built by Sembat II, late in the X. century, but his successors altered and strengthened them at various epochs during the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. From beyond the gate we see the perspective of the inner wall which has several square towers; it is in much less good repair than the outer facing. It is a most lonely, solemn scene, this wide expanse of brown earth and yellow grass with the towers and churches standing out like isolated sentries.

|

On entering the enclosure one first turns one's steps in the direction of the cathedral. From a distance it seems to be merely a plain rectangular structure with no architectural pretensions. But on closer inspection it proves to be a building of really great beauty and [page 303] of the most perfect proportions. The material used is stone of a rich rose-red, which glows in the bright sunlight, producing a most wonderful effect. It stands quite alone, for only the merest vestiges of the neighbouring edifices remain. The outer walls are very simple but perfect in their simplicity ; they form an oblong, unbroken by apse, buttress, porch, or other projection. The only adornments are the two large niches at the east end, smaller ones on the other sides, a false arcade of round arches lightly indicated covering all four walls, and a number of high, narrow, round-arched windows. The columns of the false arcade are slender and graceful, their capitals and the mouldings round the niches and windows are of delicate and tasteful workmanship. The general scheme of decoration is Byzantine, but it is much simpler than that of the famous temples of Constantinople or Ravenna. There are no human and very few animal figures to be seen, except some birds of a kind closely resembling those of Byzantine art. The commonest form of ornament is the interlacing pattern which by a skilful arrangement of deep shadows forms a most valuable decorative feature. The roof is all of stone, and indicates the cruciform plan, showing the nave and the transept with the base of a drum, also adorned with a false arcade, which formerly supported a dome, now fallen in. The interior is of extreme grandeur and stateliness. The simplicity both of plan and of decoration, the beautiful proportions, and the perfection of the lines are most striking. Although not a large building - according to Mr. Lynch the interior measures 105 feet 6 inches [page 304] in length by 65 feet 6 inches in breadth - it is very high and produces, like so many of the Armenian churches, an impression of great spaciousness and of religious solemnity. Four large piers of masonry support the dome, while two others are at each end of the church, pointed arches springing from them. The rounded apse, adorned with an arcade above the dais, is contained in the space indicated by the two outside niches at the east end. Two small apses to the north and south complete the interior. There are faint traces of paintings on some of the walls, too faded and damaged to indicate the subjects. The lighting would be very dim but for the hole in the roof produced by the collapse of the dome. The floor is covered with large stone flags. Many fragments of sculptured stone are scattered about, but most of the best specimens have been transferred to the museum. A poor little altar has been erected in one of the apses, where the old priest occasionally says mass; patriotic Armenians are wont to make pilgrimages here from time to time to listen to Divine service amidst the "bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang."

The inscriptions, which are mostly in Armenian, indicate Sembat II (977-989) as the founder of the cathedral, which was completed by Gaghik I (989-1019). Some of the legends allude to public acts of the kings or governors of Ani, and others to pious donations to the Church.

|

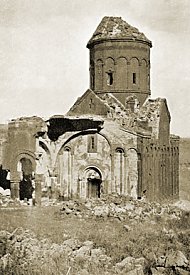

The next most important church is that of St. Gregory the Illuminator, situated on the ridge to the east of and below the cathedral overlooking the dark [page 305] gorge of the Arpa Chai. In general form it closely resembles the cathedral, but the conical dome supported on a polygonal drum and the elaborate porch have survived, although in a ruinous condition. The false arcade rests on slender double columns, and its mouldings and tracery are extremely rich and finely chiselled. The eagle pursuing a hare and other bird motifs are prominent. There are niches similar to those of the cathedral, but less pronounced, and the same arrangement of the roof indicating nave and transept. The porch is of much more solid and heavy construction and of a later date; it is formed by round, stilted arches supported on short, squat columns with beautifully carved capitals of a Byzantine type. The arches themselves have the Norman zigzag moulding, surmounted by tracery. Both within the porch and within the body of the church the frescoes, representing figures of Christ, the Virgin, and Saints, are fairly well preserved, and although of small artistic value enhance the general decorative effect.

The church was built together with a monastery, according to an Armenian inscription, by one Tigran, of the family of Honentz, in 1215, while Zakarea was Governor (in the Georgian period). As several of the inscriptions are in Georgian or in Greek characters the opinion has been expressed that it was a Greek church; but, as Mr. Lynch points out, it was built by an Armenian and dedicated to an Armenian saint.

The beautiful little chapel of St. Gregory belongs to a different type, also common in Armenian architecture It is a polygonal building (twelve sides) [page 306] supporting a round drum with a conical roof. On each side there is a window or a niche, narrow and round-arched, with a string-course going all round the building and blending with the false arch above the niches. Internally, we have the usual combination of simplicity with exquisite proportions producing an impression of loftiness and dignity. It was a sort of mortuary chapel to the Pahlavid family, some of whose members were buried here; there is an inscription by one Vahram, who personified Armenian patriotism and opposed Greek influence, and died in battle against the Kurds (1047). There are traces of many tombs. A very similar building is the chapel of the Redeemer, dating from the 11th century, situated at some distance beyond the east end of the cathedral. There are several chapels of the same order at Ani, some still standing, others only indicated by the foundations. Nor can the church of the Apostles be overlooked, which although in ruins shows signs of having been a fine building. The east front is decorated with elaborate honeycomb vaultings, false niches, and other Saracen adornments. The earliest inscriptions bear the date 1031 and the name of Apughamer, son of Vahram, while the latest is a public proclamation of the year 1348, which shows that even twenty-nine years after the great earthquake the city was still inhabited.

A very important and beautiful building is the monastery of Khosha Vank, on the opposite bank of the Arpa Chai, mentioned in the chronicles as the place where the Armenian kings often repaired to deliberate on affairs of state. But unfortunately I [page 307] did not have time to visit it, as it is some distance from Ani.

|

Of the secular buildings the most remarkable is the castle, a huge structure at the edge of the cliff, overlooking the Aladja Chai ravine at the extreme northwestern end of the town. On the inner side we see two storeys, the lower formed of three rounded barrel-shaped vaults, the upper divided into three corresponding apartments. The outer wall facing the town has collapsed and the roof has fallen in. On the other side, overlooking the valley the masonry descends further down, thus forming a higher building, and there are a number of other chambers and passages. The only piece of decoration is the doorway facing the town, adorned with beautiful carving and inlay, surmounted by a pointed arched window. I was told by the old priest that this was the palace of the Pahlavid kings, but Mr. Lynch describes this designation as "purely imaginary." It was probably part of the defences of Ani, and its outer wall is indeed a continuation of the great double wall already described. At the southern end of the town on a high mound we have the remains of the citadel-the citadel which was probably the fortress of Ani before the city was built. All that remains of it are some fragments of walls and two small chapels, one of which contains a few beautiful fragments of carving. The palace of the kings was apparently situated here.

Another large edifice is the mosque with the polygonal minaret, built by Manuchar, of the Kurdish family of Beni-Cheddad, Prince of Ani (1072), and is no doubt the earliest Moslem temple. [page 308] There are several Persian, Arabic, and Cufic inscriptions of various dates. The exterior consists of plain, unadorned walls of black and red stones, but the interior is a curious chamber with round vaultings, supported by short, thick, round columns. There is a lower chamber with windows overlooking the ravine, but below the level of the Ani plateau. It is now used as a storehouse of antiquities, and contains a number of fragments of stone carving, capitals, inscriptions, pottery, ornaments, and coins, besides a few archaeological books, plans, and drawings relating to Ani. Wandering about the deserted city one comes every moment upon some new discovery, some fresh fragment of architecture. On the sides of the cliffs there are many remains of fortifications, massive towers, bastions, and parapets, and here and there a small chapel. Right down in the gorge, not far from the ferry, are the broken piers of a stone bridge across the Arpa Chai, whence a road led up to the city ; somewhat lower down are the remains of a second. There are numerous subterranean chambers, probably storerooms for grain and reservoirs. A great deal remains yet to be excavated at Ani, for hitherto the Russian Government, in its absurd fear of arousing Armenian nationalism, has opposed any systematic exploration. Professor Marr, of St. Petersburg, is now working at the ruins, and has made many valuable discoveries, but even he is hampered by want of funds, and in the present state: of things the Government is not in a position to provide much money.

|

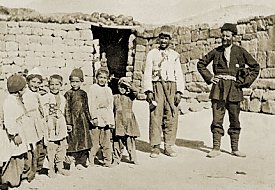

Very curious and interesting are the cave dwellings, of which there is a large number. The most important [page 309] group are those in the Aladja Chai ravine and in the little valley running up towards the depression separating the Aladja from the Arpa Chai. The Aladja ravine is much broader and less forbidding than that of the Arpa Chai, and the banks are grassy and in places cultivated, so that it would naturally be preferred as a place of residence. A whole row of caves has been dug out of the soft tufa on what I may call the Ani block, just below the castle, another on the opposite side of the little valley, and several rows beyond the Aladja Chai. A large part of the ancient population of Ani probably dwelt in them, and many are still inhabited to this day. I entered two or three, and certainly I have never seen more primitive dwelling-places anywhere. There was no overcrowding, as each family had two or three "rooms" at its disposal; but there was no furniture save couches made by cutting into the tufa, a few rags, and some cooking utensils. The dirt, the poverty, and barbarism were incredible. These Trogloddytes were both Armenians and Tartars; I have seldom met with more wretched specimens of either race. On the plain beyond the double wall, at some distance from the deserted city, is a small village, also called Ani, inhabited by Tartars, but of a superior type. They were very friendly and courteous, and I was taken into a dark, cellar-like room with no furniture, save a broad earthen divan round three sides of the apartment and covered with dirty cushions and rugs. Here a number of villagers and a few strangers, including the Armenian merchant with whom I had travelled the day before, were gathered together to chat and eat grapes. Tartars [page 310] and Armenians in this part of the country seem to live on very good terms, and although separated by religion and customs, are not at all anxious to cut each other's throats.

|

From the Tartar village I returned to the ruins, and after a meal in the hostelry I took leave of this marvellous city. It shows evidence of a building power and architectural skill on the part of the ancient Armenians of the highest order, and enables us to realize that this people, in spite of the lamentable history of the last six centuries, is a nation with a noble past. Today this spot, where proud kings once dwelt in splendid courts and held sway over prosperous lands and civilized subjects, where public life was active and vigorous, is a crying wilderness. None but the old priest and the peasant family dwell within the enclosure, and even the neighbouring country, formerly so fertile and well-peopled, is now almost uninhabited, and has become to a great extent barren desert. Is the state of Ani symbolical of that of the Armenian nation, and are they destined at last to disappear or be absorbed into other races, other religions? I do not think so, for with all the sufferings and persecution they have undergone they still preserve a vigorous national life. Many of them have been massacred, but the survivors are not absorbed. Their industry is more active than ever, and education is making great progress. They have built up the oil trade of Baku, they monopolize the commerce of Tiflis, and at Rostoff-on-the-Don, Baku, Odessa, Moscow, Kishinieff, Constantinople, Bombay, Calcutta, and many another city far removed from their [page 311] ancestral homes, they form industrious, intelligent, and prosperous commercial communities. A people with such a past and such a present need surely not despair of its future.

NOTES

1. Somewhat later a few isolated murders have been committed, but there has been no outbreak.

2. I am largely indebted to Mr. Lynch's "Armenia" for this sketch of Armenian history and for some of the architectural details of Ani.

3. "Armenia" by H. B. F. Lynch, vol. i. p. 336.

4. Ibid. p. 370.