The restoration of the Holy Cross church on Aghtamar (Akdamar) island: photographs and observations

In May 2005 the world-famous 10th-century Armenian church on Aghtamar (Akdamar) island in Lake Van was closed for visitors to allow a restoration of the monument to begin.

The restoration of the Aghtamar church is, according to the words of one of those in charge of it, "the best-quality restoration-project that has ever been undertaken in Turkey". The reality is that the Aghtamar restoration actually fails to follow acceptable modern standards and practices in almost every aspect. Restoration is the process of making alterations and repairs to a building with the intention of restoring it to its original form. Restoration is a more drastic intervention than conservation. Outrage at the damage done during ruthless "restorations" in 19th-century Europe first created codes of conduct in relation to such activities. These have progressed to the extent that today the traditional concept of restoration is now regarded as a discredited and obsolete practice that has been replaced by that of conservation. Conservation is the preservation of an existing building, taking great care not to alter or destroy any aspect of it. Any repairs must be restricted to essential repairs only, and must always respect the existing character of the building. Article 9 of the International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites states that "the aim of restoration is to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and the historical value of the monument and is based on respect for the original building and on authentic documents". The fundamental principles of modern conservation are 'minimal intervention' and 'conserve as found'. Conservation methods must retain the authenticity of the monument, use materials sympathetic to the original structure, preserve important original fabric, and apply the least visual change to a structure. The goal should be, wherever possible, to preserve the monument frozen in time. Unfortunately, a conservation-led policy of minimal intervention is not found amongst the techniques and philosophy of Turkey's 'restoration industry', which seems to be based entirely on the exploitation and trivialisation of historical buildings.

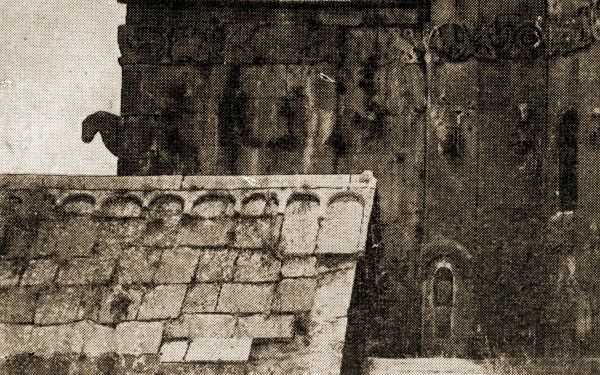

The above photograph, taken in July 2006, reveals that in addition to the zhamatun, new roofs have been placed over the chapel of Catholicos Step'anos and its porch. The finish of all this new work is clearly unsympathetic to the original structure. The photograph reproduced below also shows that it is historically inaccurate.

This photograph (plate 2 in Stephan Mnatsakanian's 1983 book Aghtamar) was taken before 1915. It shows the roof of the Step'anos chapel and reveals that the roof constructed in 2006 does not match the appearance of the original roof. Most of the original roofing slabs had been lost by the time of the restoration, but their form could easily have been recreated using old photographs as a guide. That they were not typifies the careless attitude that the restorers have taken towards the accuracy of their restoration.

Next to the church lie piles of machine-cut stone slabs, unsympathetic to the original masonry of the monument. These stones were later used to cover the floor of the zhamatun, the chapels, and the church. This "restored" paving is entirely unlike the original floor covering. The zhamatun was originally paved with a layer of flat, irregularly-shaped stones - sections of which still survived until the restoration (they are now destroyed). The original 10th-century paving of the church has not survived. At some time during its history it was re-paved using a mixture of flat, irregularly-shaped stones and reused late-medieval gravestones.

A surviving section of the original floor surface of the zhamatun, photographed in 2004.

A photograph showing the interior of the zhamatun during the restoration. All the surviving sections of the original flooring have been destroyed and a thick layer of concrete has been poured over the entire floor to act as a foundation for the new paving of cut stone slabs. Once again, the restoration has made a fundamental alteration to the original appearance of the monument.

The new floor covering, together with the new stone-clad roof, will create an airtight environment within the zhamatun that may have implications for the internal atmosphere of the church. It is likely that it will lead to a build-up of moisture, risking damage to the stonework, the mortar, and to the plaster and frescoes within the main church.

A worker uses a wire-brush to scrub the walls clean of any history and character.

There appears to be little or no archaeological element to the restoration. Layers of stratified earth are simply dug away by labourers and discarded. Any masonry fragments that are uncovered, including cut stones bearing carvings, are simply added to several big piles of debris and their original locations are unrecorded. Why did all this happen at Aghtamar?It is important to realise that the current restoration of the Aghtamar church is a political act, done for political reasons. It is the result of political imperatives rather than archaeological necessities. It may be being paid for by Turkey, but it was largely instigated by pro-Turkish elements within the EU who wanted Turkey to make a highly visible and expensive gesture that would show to its critics that all is well within Turkey regarding its treatment of minority cultures.Elements within Europe and America in favour of Turkey's admission to the EU have made lists of suggestions that Turkey should follow in order to improve its public image and thus make its application for EU membership easier. One of the suggestions (in order to neutralise the opposition of descendants of ethnic groups such as Greeks and Armenians that Turkey had committed genocide against) was that Turkey should to be able to show that it takes care of the historical monuments of its minority cultures, especially those of its vanished non-Muslim minorities. In an EU document sent to Turkey, the Aghtamar church was specifically mentioned as a building that, if it were restored, could be used as a highly visible example of how Turkey is actively preserving its non-Turkish monuments (according to information given to me by an Associated Press reporter). It is ironic that the EU's awareness of the Aghtamar church, and the propaganda value that could be gained by restoring it, arose as a direct result of the activities of certain Armenian organisations and lobbyist-groups around the world. Consistently, over the last decade, they have produced propaganda mentioning the Aghtamar church. Here are excerpts from some recent examples.

Assembly of Armenians of Europe, November 2004 press release (REF: PR/04/11/013): Marvellous carvings of the 10th century church of Akhtamar (Lake Van, Eastern Turkey) are regularly being used as targets for shooting practice by visitors... The church, which is visited by many foreign tourists, is badly neglected and close to ruins... The church has been neglected and harmed by treasure hunters and is at risk of collapsing. Both its foundation and ceiling have cracks and holes. California Courier Online, 18th November 2004: Visitors Use 10th Century Akhtamar Armenia Church for Target Practice. This article also cited a photograph purporting to show the recent damage. The photograph actually showed damage that had been there since the 1950s. Article 1 of the previously mentioned International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, in defining what an historic monument is, states that an historic monument is also physical "evidence of a particular civilisation, a significant development, or an historic event". Article 3 explains that the intention behind conserving a monument should be the preserving of historical evidence as much as any other reason. These are core values that need to be held by those behind any successful restoration. How could they have been present amongst those who planned the Aghtamar restoration, when most of the historical and cultural aspects relating to that monument are still vehemently denied by Turkey?

|