| Structure: Marr-Orbeli site 73. Other designations: Church of the Holy Mother of God; Surp Asdvadzadzin; Azize Meryem Katedrali; Fethiye Camii. History

"In the year 450 (AD 1001) of the Armenians ... at the time of Sarkis, honoured by God and Katholikos, spiritual lord of the Armenians, and during the glorious reign of Gagik, shahanshah of the Armenians and of the Georgians, I Katranideh, Queen of the Armenians, daughter of Vasak, King of Siunik, entrusted myself to the mercy of God and, by order of my husband Gagik shahanshah, built this holy cathedral, which the great Smbat had founded..."

- Part of a 21 line inscription on the southern facade of the Cathedral

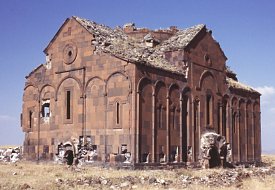

Near the southern edge of the city stands the imposing Cathedral. This is the largest and most important building in Ani, and a structure of world architectural importance.According to various historical sources and inscriptions, it is known that building work started in the year 989 under King Smbat II (977-89) and was completed, after a halt in construction, by the year 1001 (or 1010 depending on the reading of the inscription) by order of Queen Katranideh (Catherine), the wife of King Gagik Bagratuni, Smbat's successor. The cathedral was the work of Trdat, one of the most celebrated architects of medieval Armenia.

During the siege of 1064 the Cathedral held a symbolic importance. As the victorious Turks looted the city, one of them climbed the roof of the cathedral and tore down the large cross that rose from the top of the dome's conical roof. (It is said that this cross was later sealed under the threshold of a mosque so that it could be continuously tramped upon.) The Cathedral was then converted to a mosque and renamed the Fethiye Camisi, the Victory Mosque.It was returned to Christian usage in 1124, and inscriptions tell of restoration work carried out in the early 13th century. The devastating earthquake of 1319 brought down the dome and may have marked the end of the building's formal religious use.

|

|

6. The Cathedral seen from the south-west |

7. The north-west corner - 1988 earthquake damage |

The Architecture

Like most Armenian buildings, the cathedral is built entirely from stone - a facing of extremely well cut and finished polychrome masonry hides a rubble concrete core. The plan is in the form of a domed basilica. This is a pattern found in Armenia since the seventh century. However, Trdat's design takes this old form to new heights of sophistication and originality.

A decorative blind arcade on slim columns runs around the whole of the exterior, into which are inserted tall slender windows with frames of finely carved fretwork. There are also small porthole windows below the gables of each transept. There are entrance doorways in the north, south and west walls - these traditionally were for the patriarch, the king and the people respectively. Standing out in front of each doorway was originally a vaulted porch now mostly destroyed, probably a canopy resting on free-standing pillars.

The distinctive triangular niches cut into the north, south and east facades, together with the positioning of the windows, indicate the location of the transepts and apse within. These niches also break up the plain surface of the facades, and give an increased sense of height and solidity to the walls (which are actually very thin). Structurally, the niches also act like a sort of splayed buttress. There are no niches on the western facade because a greater thickness of wall is needed here to counteract the thrust of the large arched vault inside. |

|

11. A window, south facade |  12. A window, east facade |  13. Circular window, west facade |  14. Inside the cathedral |

The Interior

The inside of the cathedral is tall, and rather dark - and would have been even more so when the central dome was in place. This is not a flaw, but an intention. Since the apse and side-chambers account for about a quarter of the interior space, the vaults east of the dome are short, considerably shorter than those west of the dome. Four massive clustered piers in the rectangular nave support both the dome and the arches supporting the roof. The barrel vaults along the east-west and north-south axes are almost as high as the base of the drum, and are expressed outside in the two intersecting pitched roofs. The spacious apse is accommodated beneath the easterly roof and revealed on the outside facade only in the form of a window between two deep niches. The chancel within the apse is elevated from the rest of the floor and has a row of ten semicircular niches containing seats. It is flanked by two-storied chambers whose upper floors are reached by narrow stairs accessed from within the chancel.

|

|