History

"The giant church of Tekor has collapsed and presents a pitiful picture. The image is so disturbing that at first one needs some time to recover from the shock." - Ashkharbek Kalantar, writing in 1920

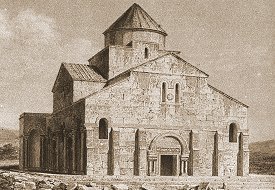

The now scant remains of this important fifth century church stand on a slope overlooking the village of Digor, formerly called Tekor, located 22km southwest of Ani. The building stood intact until the year 1912, when an earthquake caused the collapse of the dome, most of the roof, and much of the southern facade. In some books this 1912 date varies, and the cause of the collapse is given as a lightning strike. Another earthquake in 1936 caused an unknown amount of additional damage. The present condition of the remains - with only fragments of the concrete core remaining, entirely stripped of facing stone - is mostly the work of man rather than earthquakes. According to the residents of Digor, the facing stone was removed during the 1960s and used to construction the Digor town hall. This building was demolished in the 1970s and the fate of the stone is unknown. An inscription on the lintel over the western entrance described the structure as "this Saint Sargis' martyrion" and said that it was built by Prince Sahak Kamsarakan and consecrated by the Patriarch Yohan Mandakuni. The mentioning of these individuals dates the church to the 480s. This inscription was the oldest known example of Armenian lettering and ran, unusually, from bottom to top. The building was restored during the time of the Bagratids, at which time it was known as the Holy Trinity church. DescriptionThis church is now generally held to be the earliest known domed Armenian church.Formerly it was believed that the church was built as a basilica without a dome (possibly of pre-Christian origin and converted to a church by adding an apse) and that the dome was added later; as late as the seventh century according to some. According to current opinion, the church was build from the outset as a domed building with a "cross within a rectangular perimeter" plan.

The church originally had four entrances: one to the west, one to the south, and two to the north. At a later period these doors were closed off, except for the western most entrance on the northern side which was reduced in size. These doors were framed by visually powerful portals of horseshoe arches resting on jambs of twin embedded columns. These columns had carved capitals of jagged, and very stylised, acanthus leaves. The lintel over each door was carved with a strange, swirling palmette motif. All the larger windows were reduced in size at some distant period, possibly during the Bagratid restoration (the external pyramid roof of the dome probably also dates from this restoration). Oblong rooms flanked each side of the apse. The walls of these rooms extend outwards from the north and south facades, a feature that is also found on other early Armenian churches of this period. At the north-eastern corner of the church, set into the external wall of the northern of these rooms is a semicircular niche, probably a baptismal font. The church stood on a nine stepped base. Because this base is wider than the church, it used to be thought that a portico once ran around the outside of the church, supported on the pilasters and columns that are attached to the lower half of the facade. The position of the windows and the height of the north-eastern niche with its baptismal font tend to contradict that theory. The pilasters may just be decorative, a feature also found in Syrian architecture from this period. Another indication of possible Syrian influence is the moulded band that ran around the three facades and over the arches of the windows. |

1. The Tekor church - an engraving from the 1840s

|