|

The Town of Tomarza Tomarza is a small town in central Turkey with around 10,000 inhabitants. It is located about 42km to the southeast of Kayseri. Tomarza may lie on the site of an old Byzantine settlement. The last Armenian king of Kars was given these lands in 1064 in exchange for ceding Kars to the Byzantine Empire. The first recorded mention of Tomarza is from 1206 as the place of origin of the scribe Gregory the Priest. According to a local tradition, thirteen noble Cilician families founded Tomarza after the fall of the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia in 1375. Tomarza was divided into four quarters, each governed by a different family who were closely linked by intermarriage and who also possessed a share of the villages that surrounded the town. These four families acted together to run the town and its territory -this autonomy continued until the establishment of the 1908 Ottoman constitution. About 4000 Armenians lived in Tomarza in 1915, and they comprised the vast majority of the town's population (there were only 25 Turkish families). In August 1915 the entire Armenian population was deported. Some Tomarza Armenians who survived the massacres and deportations returned to their native town in 1919 but they had all left again by the late 1920s. Part of the surviving community migrated to America and settled in Racine, Wisconsin, where some Armenians from Tomarza had established themselves in the years prior to the Genocide. Descendants of Tomarza Armenians still live in Racine. The "Church of the Panaghia" at Tomarza The most important monument in Tomarza used to be the ruins of an early Christian church. It is now entirely destroyed, but was still standing in 1909 when Gertrude Bell photographed it and described it as "extraordinarily interesting, showing strong Hellenistic influences, and altogether very enigmatic" [see note 1]. Prior to this, Hans Rott had visited Tomarza in June 1906 and later published a groundplan of this church. Rott's account was the first to use the appellation "Church of the Panaghia". The plan below is based on that of Rott's.

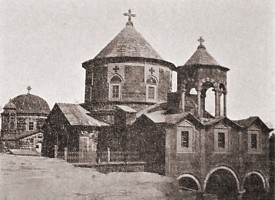

The church had a cross-shaped plan with a dome over its central axis and probably dated from the late 5th century or early 6th century [see note 2]. It was one of a group of domed churches in Byzantine Cappadocia that may have influenced the early development of domed church architecture in Armenia and Georgia. The church was demolished in the early 1920s (in 1954 local inhabitants told Richard Krautheimer it had happened in about 1921), an act perhaps connected to the expulsion of Kayseri region's Greek population. The Monastery of Surp Astvatsatsin In the 19th century Tomarza was renowned locally for its Armenian monastery dedicated to the Holy Mother of God, (Surp Astvatsatsin). The monastery was an important pilgrimage centre and each August thousands of people would gather there for the Festival of the Assumption. The earliest mention of the Surp Astvatsatsin Church of Tomarza is in a colophon of 1516. After that date the name of Surp Astvatsatsin appears frequently. In the 1570s and 1580s the monastery became a important centre of culture due to the efforts of Bishop Astuacatur of Taron. At that time the monastery served as the seat of a bishop whose jurisdiction extended over Tomarza and nearby villages. From 1784 to 1915 priors headed the monastery, and at the end of the nineteenth century a boarding school was established within its premises. In June 1909 Gertrude Bell stayed a night at the monastery, in a "splendid great room with many windows facing Mt Argaeus". The monastery was looted in 1915 and then abandoned. Although badly damaged, it was re-occupied by some Armenian monks in the years immediately after the First World War. H. E. King, writing in 1939 after a visit to Tomarza, said that the monks had been "ejected within the last decade" but mentioned nothing about the condition of the monastery's buildings. Buildings within the Monastery Precincts The oldest building in the complex was a small church built against the side of the adjoining hill. The sanctuary was dedicated to the Holy Mother of God and was called Surp Astvatsatsin. Gertrude Bell wrote that the church was 800 years old, but its dome on pendentives had been rebuilt at a later period. Inside the church were five old tombstones, the two earliest ones bore the dates 1607 and 1608. The interior walls of the church were decorated with blue tiles. In 1822 a chapel dedicated to Surp Karapet (St. John the Precursor) was built to the immediate south of Surp Astvatsatsin. Because of its small size this chapel was referred to as a vestry, and was on a lower level by a few steps than Surp Astvatsatsin. From 1849 to 1851 a new church was constructed a little to the south-east of Surp Astvatsatsin. It was called Surp Khatch (Holy Cross) and was a large cruciform structure with a dome supported on a drum resting on pendentives. The interior of the church was covered in figurative frescos. In front of the church was a two-story narthex with a bell-tower and a portico open to the west. According to an inscription, when the church was being constructed the entire monastery was also renewed. Most of the monastery's ancillary functions were housed in a substantial two-story structure located to the west of the churches. This building contained a guesthouse with two halls, six rooms, and thirty-five cells for monks and pilgrims. The monastery also had a library, kitchen, pantry, refectory, and storerooms. The monastery possessed thirty pieces of arable land - over 1000 acres - in the vicinity of Tomarza, and had a garden, mills, barns, and stables. The entrance to the guesthouse complex was a structure on two stories that protruded out from the main façade. The precinct of Tomarza's "Merkez Camii" mosque has a gateway that is so similar that the same architect must have designed both (compare photographs 4 and 10). In the grounds of the monastery Gertrude Bell noted many enormous old stone slabs with crosses on them, and some with Armenian inscriptions. Very little now remains of the Surp Astvatsatsin monastery. Its ruins are located at the eastern edge of Tomarza. They consist of some foundations of the eastern end of the Surp Khatch church and some fragments of the Surp Karapet church. Photograph 11 was taken from a similar position as photograph 6. Nothing at all is left of the monastery's ancillary buildings. On the road leading to the monastery is a house whose walls contain many fragments of Armenian gravestones. |

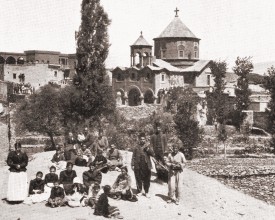

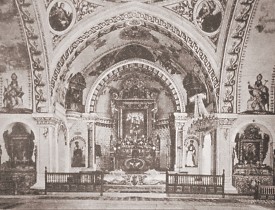

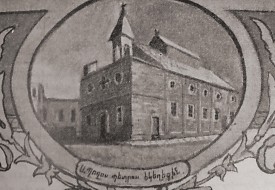

1. Tomarza's "Church of the Panaghia" seen from the southeast - photographed by Gertrude Bell in 1909  2. The south facade of the "Church of the Panaghia" - photographed by Gertrude Bell in 1909  3. The monastery of Surp Astvatsatsin seen from the southwest - photographed by Gertrude Bell in 1909  4. The main entrance and guesthouse of the monastery  5. Inside the precincts of the monastery, showing the main church - photographed by Hans Rott in 1906  6. Pilgrims gathered inside the monastery precincts  7. The east ends of Surp Astvatsatsin and Surp Khatch  8. The interior of the Surp Astvatsatsin church  9. The narthex and belltower of Surp Astvatsatsin  10. The gateway to the Merkez Camii mosque  11. In 2006 this was all that remained of the monastery  12. Another view of the ruins of the monastery  13. Probably a fragment of the Surp Astvatsatsin church |

14. Foundations of the external wall of the apse of the Sourp Khatch church |  15. A niche within the remains of the apse of the Sourp Khatch church |  16. A column base (not in-situ), perhaps from the narthex of Sourp Khach church |

The Church of Surp Poghos-Petros The Saints Poghos-Petros (or Boghos-Bedros) church (church of Saints Paul and Peter) is first mentioned in 1570. In the early decades of the nineteenth century this church was a small and semi-dilapidated chapel. In 1837 the Armenians of Tomarza erected in its place a magnificent new church built of stone. It stood in a location where the four main quarters of Tomarza converged. In the centre of Tomarza, in the district of Cumhuriyet mahallesi, is a large, derelict Armenian church. It is almost certainly the Poghos-Petros church. There remains a small doubt about this identification because some old descriptions of the Poghos-Petros church do not seem to correspond with this building [see note 3]. The church was used as a municipal warehouse during the 1990s, and photographs from that period show the floor covered with equipment, oil drums, scrap metal, and assorted junk. The interior is now completely empty. Architectural Description The church from the outside is a plain, rectangular structure, and is well built using large blocks of stone. Parts of the façade incorporate re-used Armenian gravestones. The western end of the church is badly disfigured because of the total loss of its entrance narthex and the blocking of the exposed nave and side aisles using rubble masonry. A depiction of the destroyed narthex can be seen in photograph 19. The side walls of the destroyed narthex were as high as those of the church, but its roof was lower and appears to have been flat or almost flat. The method in which the central nave was joined to the narthex is puzzling: there is no trace of a roof-line placed against the transverse arch of the nave, and the available space would seem to be too small for a conventional roof anyway. It may have been that an unorthodox method was used - perhaps panes of glass filled the arch opening, or the adjoining part of the narthex roof had a glass covering in the form of a roof light. The interior of the church takes the form of a basilica: it has a nave that is flanked by side aisles and ends in a semicircular apse with a half-dome vault. Four arches supported by a row of three cylindrical columns separate the nave from the side aisles. The ceiling of the nave is divided into four bays. The easternmost bay is a barrel vault, the bay immediately to the west of it has a groin vault, and the two remaining bays also have barrel vaults. The plan below is mostly based on the published plan by Güner Sağır.

The ceilings of the side aisles are also divided into four bays, each with a barrel vault. At the eastern end of the side aisles an arched opening leads into rectangular chambers that flank the apse. Although these chambers are now open to the aisles, a pre-1915 photograph [see photograph 22] shows them closed off, either with a wall or some sort of screen. The apse has a raised chancel. The pre-1915 photograph shows that it once contained a high altar surmounted by an ornate altarpiece. Inside the apse are two small doorways that give access to narrow staircases. These staircases led up to rooms above the side chambers (the floors of these rooms have been removed and access is not possible). Each of the upper-floor rooms originally opened onto a small, pulpit-like balcony that looked out over the side aisles. In the north and south walls is a row of four rectangular windows, now blocked up. They are positioned to be on the transverse axis of the internal bays. A second row of windows, this time circular, is positioned directly above the rectangular ones. They remain unblocked. The corner chambers were lit by a fifth rectangular window in the first row. There are no windows in the apse, but there are two circular clerestory windows above the vault of the apse. Similar circular windows light the north and south side aisles. At the top of the western end of the nave is a quatrefoil shaped window. The Frescos The church's interior is covered with flamboyant and theatrical frescos done in vivid colours. These frescos are almost exclusively architectural in nature, with many trompe l'oeil effects using neo-classical and baroque motifs. There is very little overt religious iconography depicted in the frescos and they appear to have had no figurative representations. This is in marked contrast to the interior of the Surp Khatch church in Tomarza's Surp Astvatsatsin monastery [see photograph 8] and most other Armenian Apostolic churches from this period. The north and south walls are divided horizontally using a painted cornice from which hang purple drapery trimmed with yellow tassels. Above the cornice are rectangular panels. The columns have simple impost capitals with small volutes. Painted decoration has been applied to make them appear more elaborate: a band of acanthus leaves, then egg and dart mouldings, then a palmette frieze [see photograph 27]. Heavy scrollwork covers the undersides of the nave arches. At the apex of the barrel vaults of the nave and side aisles are roundels of acanthus leaves. The groin-vaulted bay in the nave was probably meant to be a substitute for a dome. It is given emphasis by its more complicated roof and by having clerestory windows [see photograph 28]. The frescoes on the groin vault are particularly elaborate. There is a roundel of acanthus leaves at its apex, and in each segment of the vault are motifs set inside baroque-style circular frames. Those in the east and west frames are identical [photograph 29]. In the middle of the frame is a golden chalice. It contains a circular or spherical object on which is inscribed a cross. Rays of light shine out from the circle. The chalice is flanked by pairs of books whose covers are emblazoned with an embossed cross. These probably represent the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, or the first four books of the New Testament. The north and south frames also contain identical subjects [photograph 30]. An empty cross is depicted; on the head of the cross are the Armenian letters HITY. This is the Armenian equivalent of INRI, the four initial letters of the Latin words "Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum" (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews). Leaning against the cross are various items mentioned in the Crucifixion narrative, including a pole with the sponge soaked in wine and water, a ladder, and a spear. Little now remains of the frescos in the vault of the apse. The surviving fragments suggest they were architectural in nature: a trompe l'oeil representation of a coffered dome with cartouches inside each coffer. At the apex of the dome is a depiction of a flying dove behind which rays of light emanate [see photograph 32]. Around the edge of the apse vault is a painted inscription in Armenian [see photograph 31]. It translates as "This is the table of holiness and here is Christ, the sacrificial Lamb of God". The fresco scheme visible today was not the church's original scheme. An older layer of frescos under the current ones is visible in parts of the building. These older frescos are also architectural in nature, but they have a blander design and are done in less vivid colours. NOTES: SOURCES: PAGE HISTORY: |  17. The disused Armenian church in Tomarza that has been identified as being that of Surp Poghos-Petros  18. The southwest corner of the church  19. An old drawing, from before 1915, showing what the destroyed narthex of the church had looked like  20. A blocked window in the south facade  21. The interior looking along the nave towards the apse  22. Inside the church - a photograph taken before 1915  23. Looking towards the southeast corner of the church  24. The northeast end of the north aisle  25. The south aisle, some columns and arches of the nave, and part of the barrel-vaulted ceiling of the nave  26. Frescos on the south wall of the church  27. One of the painted capitals  28. The groin-vaulted bay in the ceiling of the nave  29. Detail of a fresco on the groin vault  30. Detail of a fresco on the groin vault  31. Half dome of the apse and the painted inscription  32. Detail of the dove fresco at the top of the apse |